Gestures: connecting the digital musician to their audience

introduction

Have you ever been to a performance and walked away feeling exhausted because you have been totally engaged in the performance? You have lived every moment of the performance and felt every little nuance of expression to experience an amazing performance. This experience is the power of gestures and how well they are performed can be the difference between a great and just a good performance. Digital musicians have always been criticised for their lack of engagement in their performance and this report will look at how Soundscape can provide an interface for them to be a part of the performance.

effective musical communication

A performance of any kind can be technically brilliant but if the appearance or the gestures presented by the performer is incorrect it will send the wrong message to the audience and may detract from the experience of the performance. Research into the effectiveness of musical communication of a performance equates gestures as a form of body language that can be compared to the use of hand gestures, verbal and facial expression that reinforces the words being spoken (Dahl & Friberg, 2003); (Vines, Krumhansl, Wanderley, Dalca, & Levitin, 2005). These gestures provide an integral part of the conversation and give greater meaning to what has been said.

A similar effect is often seen when watch a true virtuoso performer in a concert performance or a great front man at a rock concert. Their gestures are vital to the performance. They live and feel every aspect of the music and move expressively while playing and (Wanderley, Vines, Middleton, McKay, & Hatch, 2005)describes watching a clarinettist sway, bend knees and even move eyebrows and face to add expression to the music and make the connection with the audience. A similar description is of a Rock musician who can drive an audience into a frenzy by their movements on stage (Krenske & McKay, 2000)

Enter the twenty first century and the era of the millennial who all knew how to manoeuvre their way around a mobile device before they could talk. With this development of the mobile device you have this new form of music composition – the iPad. Research into this new genre of music has presented many questions as to its validity as a form of music and the performers engagement.

checking emails

The image of a person standing in the middle of a stage with an iPad making interaction with the small screen doesn’t scream out as an exciting performance. (Bown, Bell, & Parkinson, 2014) recall conversations with audience and their dismay at the opacity of the performers activity and questioning how live the performance actually is. Some people reviewed an iPad performance and commented that they might as well have been checking their emails mid performance (Schiavio & Høffding, 2015). The performance is seen as motionless and was considered it would be better to listen to a CD as we then could imagine the gestures a performer may make.

Working on this collaboration with the UQ Music Department iPad ensemble the challenge was to make their performance more engaging for them and the audience alike. Dr Chris Perrin (the director of the iPad ensemble) feels the challenge of working with a digital instrument is that it has limitless possibilities and with a plethora of attachments and multitudes of ways to use the device and make amazing sounds but it can be stereotyped into just an iPad and there needs to be more exploration into making the performer and the performance more engaging.

enter soundscape

Soundscape brought to the iPad Ensemble the chance to work on a different way of playing digital music and using more than musical technology to create a professional and engaging composition. The goal of the project was to build a connection between the digital musician and the audience. To achieve this the plan was to transfer the interactions they would perform to create effects from the small screen and put them one a bigger screen. One of the musicians loved the idea that the interactive surface is bigger because he had trouble with the iPad because of the size of his fingers.

The interaction with Soundscape is completely through the use of gestures. The question we posed was - what gestures made sense to the performers in creating a specific sound effect and how would that transfer to them interacting with the screens? It was important to the members of the ensemble that the gestures they wanted were similar to those of the iPad – sliders, swiping left or right, twisting knobs and tapping.

Being an instrument that had some flexibility in its structure it was interesting to explore the effects of applying more or less tension on the fabric. This was an interaction that wasn’t natural to them and brainstorming found many different possibilities that could be possible – how far do you need to stretch the fabric and can we make the fabric bounce to create an effect. All were possible gestures that could be used in making a composition.

observations

The observations from testing and people generally interacting at various performance opportunities presented different results. Many would simply touch the screens lightly and be despondent when there wasn’t a massive change in the music. There would be the repeated touch and then another which often lead to the question – How does it work?

The main issue is that people would want an immediate response. Even the iPad Ensemble initially wanted that instant recall of their actions and then realised that the music they created was in Ableton Live and it has a quantize mechanism that pulls all the music to the first beat of the bar or phrase and therefore a delay in the action. They understood this and worked this into their performance but general public are less forgiving and want it to happen now!

visual information

People have expressed the importance of visual information when performing music (Davidson, 2012). When they perform a gesture and they want to hear the result of that gesture. This feedback to the performer provides them with the answer to whether they have performed correctly and providing cues to proceed to the next action.

Another important point from the early discussions with the ensemble musicians was the nature of the gesture and that the type of gesture matched that of the sound they were hearing. This was equally apparent when a child started playing the screens like a drum to get a percussive sound and when it didn’t make the sound of the drum repeatedly beat faster and harder. The successful communication by the interface that matches the gestures is necessary to provide a desired response which in turn can leads to a successful performance that makes sense to the performer.

From the audience perspective, this matching of the gestures to the music is equally, if not more, important for the communication of the digital musician’s expressive performance. (Davidson, 1993) and (Morrison, Price, Smedley, & Meals, 2014) observations of laptop musicians and Disc jockeys explained the importance of vision to providing information about expressiveness. The right movements/gestures are important to presenting the expressive nature of the music. There is a disconnection when the expectation of a long, arching gesture creates a fast-thumping beat and similarly tapping on the screen does not provide the crashing percussion as desired.

future directions

The future direction of Soundscape is to build on the feedback gained so far about the effectiveness of the responsive nature of the interactive interface. Moving forward we want to build an interface that is responsive to touch and will change or create music instantaneously sending the correct message to the musician and the audience.

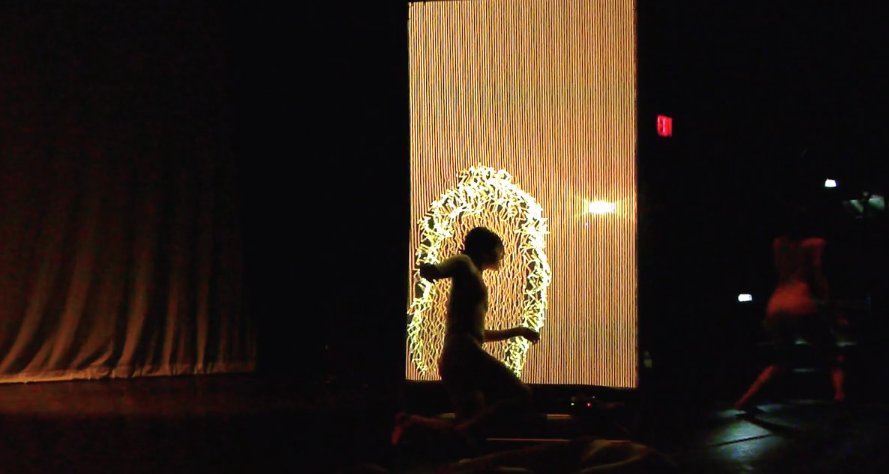

Two existing installations that provide inspiration are Aaron Sherwood’s “Mizaru” and “MICRO Double Helix”. Both installations are sensitive to touch and provide instant feedback to the people interacting with them. Both use sound and colour to grab people’s attention and maintain their interest.

Mizaru is similar to Soundscape in that it uses an interactive surface and when you touch the surface it springs to life and immerse the person into a new world of sound and colour. Exploring various themes, it can provoke deep thought and also cater for the young and playful nature of children. It is a highly visual concept which is heighten by the inclusion of people or performers as part of the overall spectacle.

The interactive spheres of MICRO – Double Helix create sound and light across a bridge in Scottsdale, Arizona. The lights are instantly responsive to touch and the music that accompanies the interaction provides the person and those around them with a response and an associated emotion that goes with the response.

The common features that intrigue people with these installations are the interactivity they generate through gestures whether that be a touch of a screen or ball, a swipe across the length of the Lycra surface or an accidental body slam into a sea of colour. The sound generated is immediate and matches the gestures the person is creating so they become part of the spectacle and those in the audience almost feel like they are drawn into the spectacle as well.

Soundscape successfully provided the opportunity for the musician to step out from behind the iPad and be part of the spectacle of the performance.

visual effects

A key element of the Aaron Sherwood installations was the use of visual effects and how successful he was in matching a gesture to a sound and a visual representation of that sound. This marrying of sound and images was highlighted in the research undertaken by (Geeves & Sutton, 2014) who studied the crowds at concerts. They studied the crowds at Rock concerts and dance parties and found the audience move expressively to the music and visuals. As the performance of a digital musicians is fundamentally different to that of a traditional musician they are choosing to use powerful imagery to match the music and allow the audience to express their feelings to the performance.

going forward

Steps forward will see us running a series of workshops that will involve people from different backgrounds and experiences. They will interact with Soundscape and provide feedback about their experience using the interface and what are their different needs and requirements to be able to create music.

From here we will take the feedback and further develop Soundscape and invite one or two of the groups back to perform again so we can evaluate the effectiveness of the development.

The goals of further development are to make the surface more spontaneous to the gestures by the performer and marry these to appropriate music and visual effects. The performer is to be an integral part of the performance and their gestures present a highly expressive message that they part of this live performance and they are too busy being expressive to check emails.

references

Bown, O., Bell, R., & Parkinson, A. (2014). Examining the perception of liveness and activity in laptop music: Listeners’ inference about what the performer is doing from the audio alone.

Dahl, S., & Friberg, A. (2003). Expressiveness of musician’s body movements in performances on marimba. In International Gesture Workshop (pp. 479–486). Springer.

Davidson, J. W. (1993). Visual perception of performance manner in the movements of solo musicians. Psychology of Music, 21(2), 103–113.

Davidson, J. W. (2012). Bodily movement and facial actions in expressive musical performance by solo and duo instrumentalists: two distinctive case studies. Psychology of Music, 40(5), 595–633.

Geeves, A., & Sutton, J. (2014). Embodied cognition, perception, and performance in music.

Krenske, L., & McKay, J. (2000). “Hard and Heavy”: Gender and Power in a heavy metal music subculture. Gender, Place and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography, 7(3), 287–304.

Morrison, S. J., Price, H. E., Smedley, E. M., & Meals, C. D. (2014). Conductor gestures influence evaluations of ensemble performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 5.

Schiavio, A., & Høffding, S. (2015). Playing together without communicating? A pre-reflective and enactive account of joint musical performance. Musicae Scientiae, 19(4), 366–388.

Vines, B. W., Krumhansl, C. L., Wanderley, M. M., Dalca, I. M., & Levitin, D. J. (2005). Dimensions of emotion in expressive musical performance. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1060(1), 462–466.

Wanderley, M. M., Vines, B. W., Middleton, N., McKay, C., & Hatch, W. (2005). The musical significance of clarinetists’ ancillary gestures: An exploration of the field. Journal of New Music Research, 34(1), 97–113.